The Leach Bar and Mikuni-so Two Mingei (Folk Crafts) Rooms Created by Tamesaburo Yamamoto.

Leach Bar 60th Anniversary Special Feature Vol. 1

The predecessor of the RIHGA Royal Hotel—the Hotel New Osaka—was established in 1935, and the Osaka Royal Hotel, designed by Isoya Yoshida, was completed in 1965.

The Leach Bar, which opened at the same time as the Osaka Royal Hotel, celebrates its 60th anniversary this year.

To mark this milestone, we present this “Leach Bar 50th Anniversary Special Feature,” originally published in the 2016 summer issue of the magazine The ROYAL.

About 40 years before the opening of the Leach Bar, one room of Mikuni-so became a base for early Mingei activities.

Mingei is a coined term meaning “folk crafts, i.e., utilitarian handcrafted art for the people.” Soetsu Yanagi, Kanjiro Kawai, and Shoji Hamada formed the core of the movement, which strove to prevent the loss of folk craft (handicraft) culture, called attention to its beauty, and advocated that correctly preserving and nurturing Mingei culture was essential for a richer life.

In 1928 (Showa 3), Yanagi and his colleagues showcased the “Mingei-kan” exhibition hall at the Commemoration of the Enthronement Ceremony: Domestic Products Promotion Tokyo Exhibition held in Ueno Park, Tokyo, with support from Tamesaburo Yamamoto—a central figure in Kansai’s business world who later became president at the founding of the Osaka Royal Hotel (predecessor of the RIHGA Royal Hotel)—and other backers. When the exposition ended, Yamamoto, reluctant to see the building disappear, purchased it and its furnishings with his own funds and moved it to his own residence in Mikuni, Osaka. The Mingei-kan, now relocated to Yamamoto’s estate, became known “Mikuni-so” after the local area.

About forty years later, during planning of the Osaka Royal Hotel (which opened in 1965, Showa 40), Yamamoto, who had become president, conceived the idea of creating a room within the hotel inspired by Mikuni-so. He consulted Isoya Yoshida, the master of Japanese architecture who designed the hotel, and entrusted the creation of this “Mingei room” to Bernard Leach, a British potter who, like Yamamoto, had a deep understanding of Mingei and was his long-standing friend.

Mikuni-so and the Leach Bar—what lies at the heart of these two Mingei rooms, connected through Yamamoto? Editor Hiroki Ko, a longtime patron of the Leach Bar, traces their background in this Leach Bar 50th anniversary special feature.

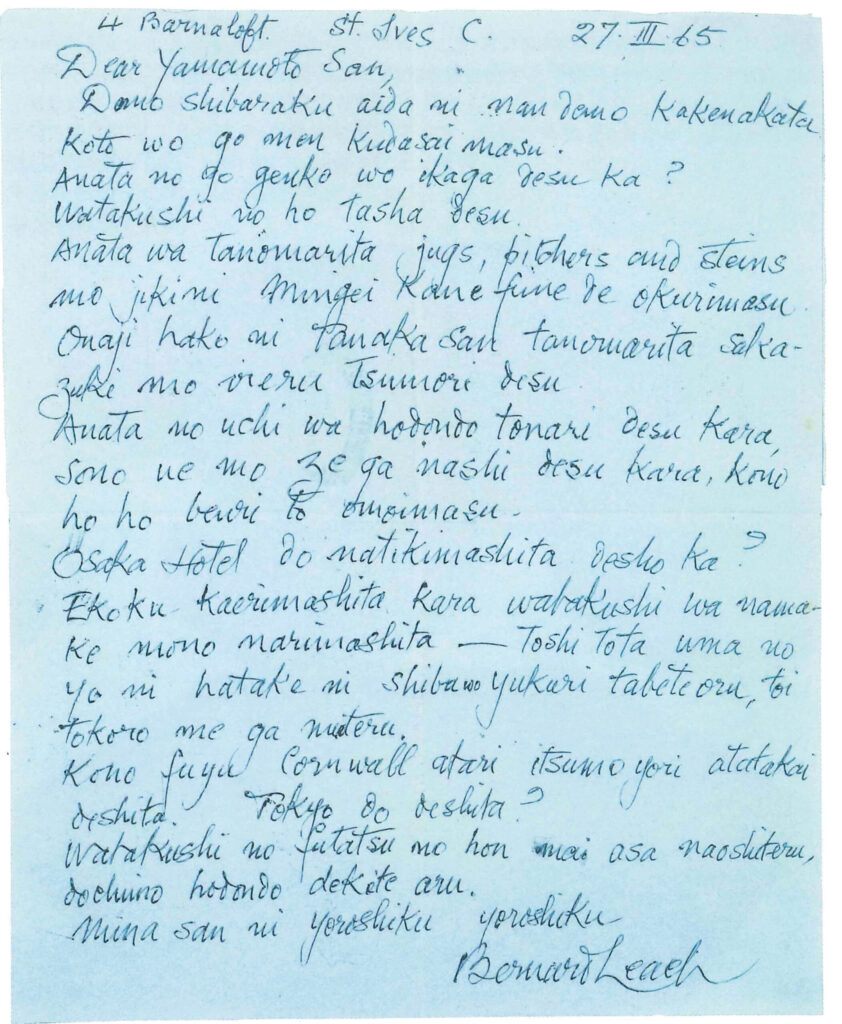

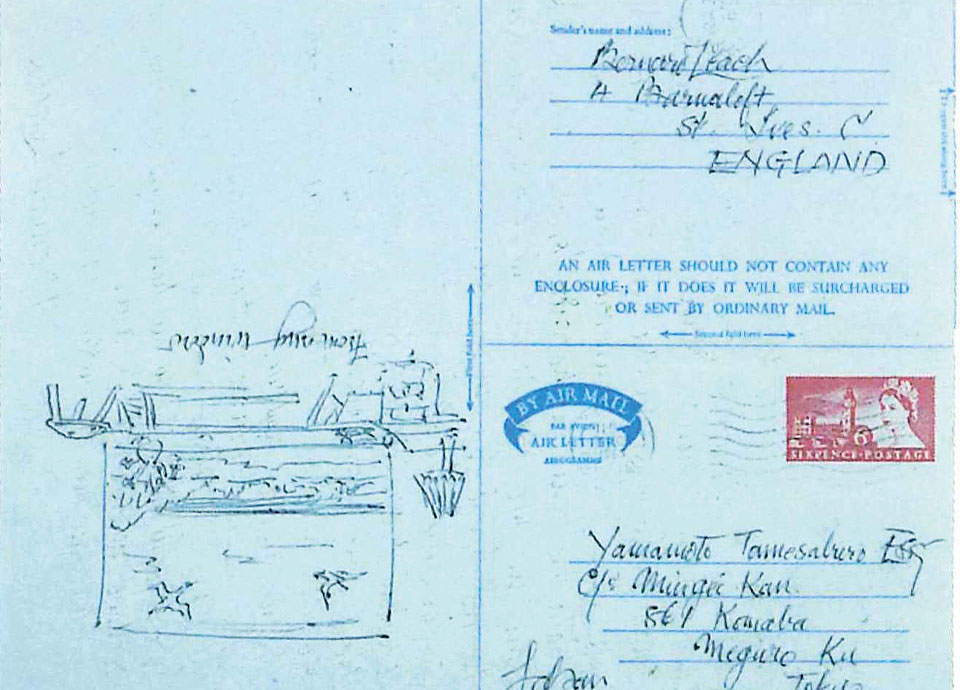

This letter was sent from St. Ives, England. Written in Japanese in Romanized script, it mentions the works Leach created at Yamamoto’s request and sent by ship, and also expresses concern about an Osaka hotel (probably regarding progress of construction of the Osaka Royal Hotel). The letter was written about ten months before Yamamoto passed away, and gives a sense of the lifelong closeness between Leach and Yamamoto.

From Mikuni-so to the Leach Bar: Embodying the Mingei Movement.

Before I knew it, I had been encountering works of the Mingei Movement for a long time at the Leach Bar of the RIHGA Royal Hotel. Here, rather than “decorating with” or “exhibiting” art pieces, it feels more accurate to say they are simply “placed.” That expression fits well because this bar was conceived in a way that is completely different from the typical hotel lounge.

This is a room where British and Japanese styles blend. More than just a commercial bar, or a space designed to attract attention with its decor, it realizes the beauty of utility. I came to understand this when I first did research for an article I wrote about this bar for a magazine about twenty years ago.

When you take a seat near the entrance of the Leach Bar, you notice a photo hanging on the wall. From the back left, you can see the faces of Isoya Yoshida, Bernard Leach, and Tamesaburo Yamamoto. The figure with his back turned is Shoji Hamada. This photo was taken before the Leach Bar came into being. Inside the bar, a photo of Soetsu Yanagi is also displayed in remembrance, as he passed away before the bar opened.

The main gathering place for Mingei colleagues was reportedly Kanjiro Kawai’s home in Kyoto’s Higashiyama district. Kawai’s piece “Large Plate with Cobalt Blue Brushstrokes” is immediately visible when you stand at the entrance of the Leach Bar, making time spent here feel special.

I’ve been coming to this bar often since my twenties, sometimes staking out a spot at the counter with my drinking friends, and often using the table seats for meetings. That’s why I’ve seen the mugs hanging in a row behind the counter, and the ceramic plates and jars placed against the wall woven with thick, slanted rattan. But they weren’t art pieces to me—just things I’d casually notice and think, “Hmm…” It seemed to represent my mind at that moment.

Glancing up behind the bar from a counter seat, you notice twelve simple-looking pitchers and mugs spaced evenly apart. They say these were actually used sometimes when the bar first opened. The pleasant tension created by the brightly polished bottles, together with the mugs and pitchers that somehow have the warmth of the human touch, gives the Leach Bar its unique ambience.

According to Soetsu Yanagi, “the Mingei Movement began when we simply stated the nature and value of the beauty found in everyday objects used by ordinary people,” and “Mingei is the product of anonymous craftsmen, not the work of artists as creators.” At the Leach Bar, I found myself perfectly immersed in what the Mingei Movement set out to achieve.

The carpet laid out on the floor apparently prompted a scolding from a customer soon after the Leach Bar opened, who said, “A luxurious carpet like this should be hung on the wall.” This episode is symbolic of the Leach Bar, which was created not as a work of art but as something beautiful yet practical, embodying the Mingei Movement’s concept of the beauty of utility. The textures of the chairs and floor also radiate a beauty shaped by long years of use.

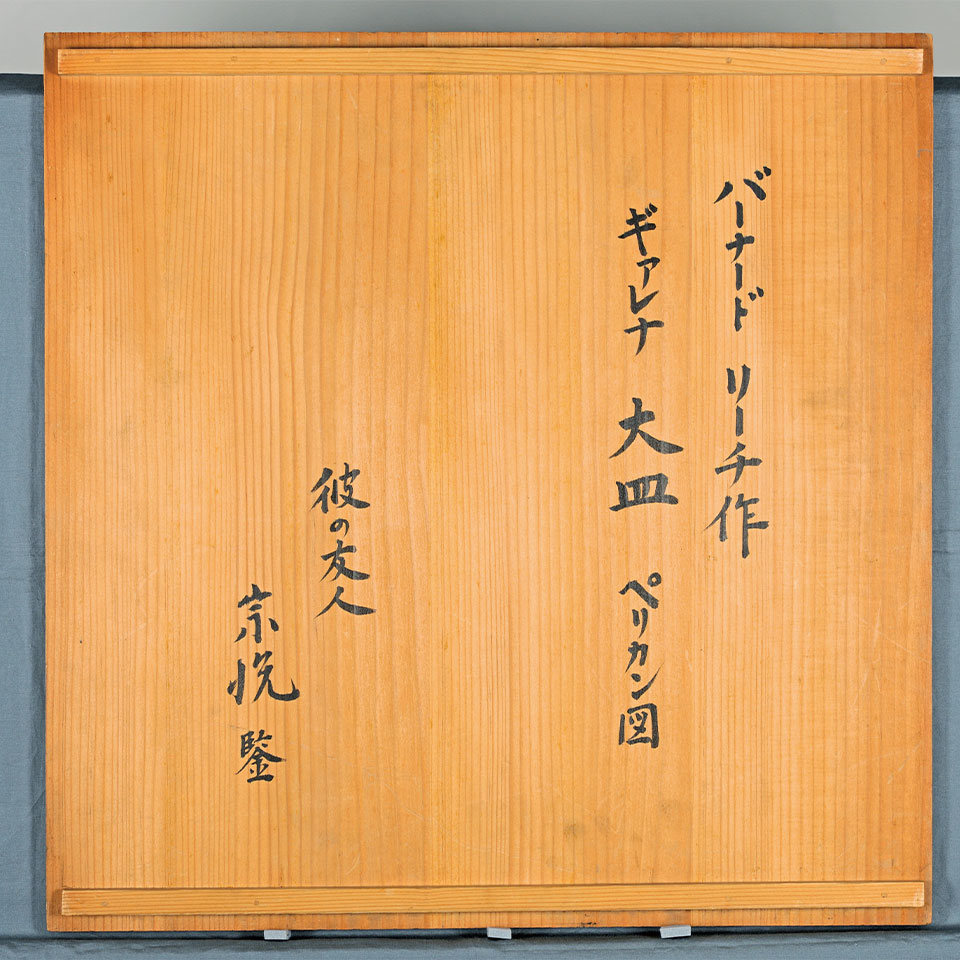

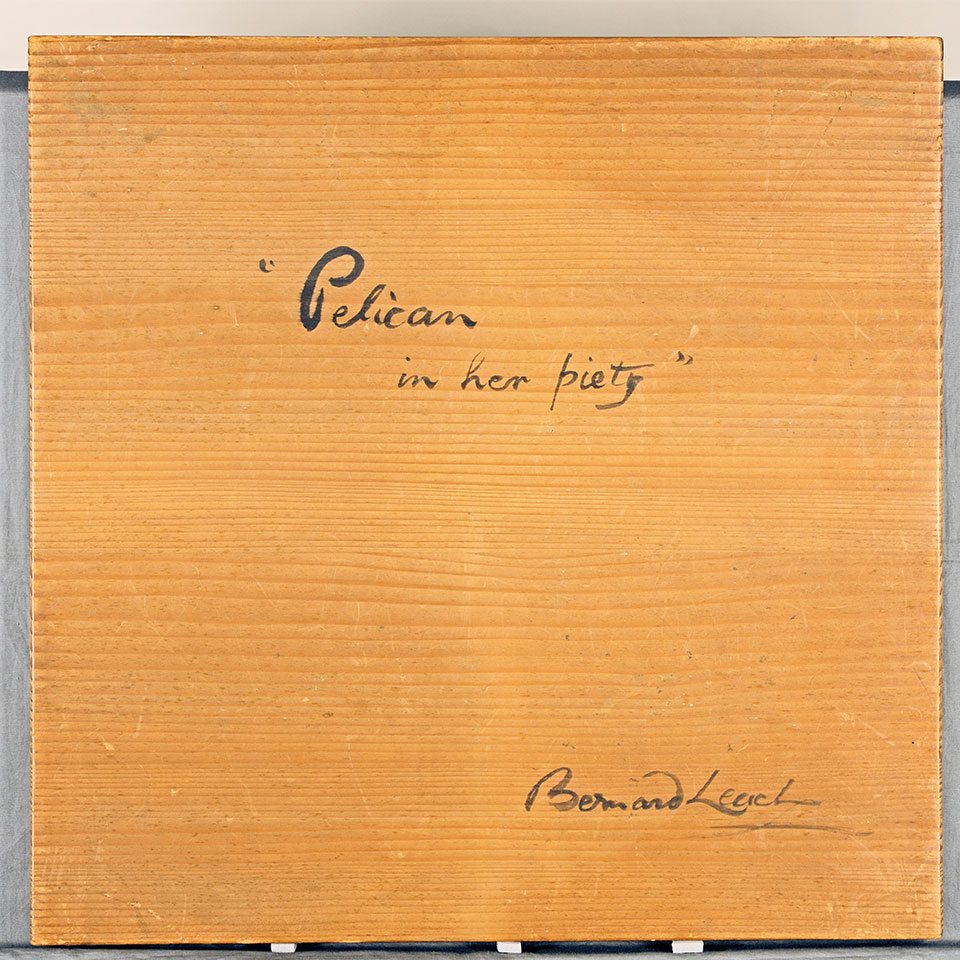

Dish with Pelican Motif,’ by Bernard Leach (1930), collection of the Asahi Group Oyamazaki Villa Museum of Art Slipware flourished in 18th-century England before falling out of favor, but Leach, through his extensive research into ceramics, revived this nearly forgotten technique in his own pieces, much like the spirit of the Mingei Movement. This piece was moved from Mikuni-so to Tamesaburo Yamamoto’s residence in Shibuya Ward’s Konno-cho around the time he established his base in Tokyo, and it adorned the guest room. Later, the dish was returned to Mikuni-so, where it fortunately escaped wartime destruction and is preserved today as one of Leach’s representative pieces.

When we engage with Mingei, we don’t need to know the creator’s background or the circumstances under which the piece was made. Still, I found myself drawn to the unique presence these things have, and before I knew it, I wound up at Mikuni-so. Mikuni-so was part of the Tamesaburo Yamamoto residence, and a place alive with the real, everyday lives of Yamamoto, his family, and the figures who embodied the Mingei Movement. In other words, it was an ideal place where Mingei itself truly existed.

Mikuni-so, temporarily restored for a limited time.

Although Mikuni-so can no longer be seen today, from the end of 2015 to spring 2016, its appearance was recreated and exhibited for a limited period at the exhibition “50 Years Since the Passing of Tamesaburo Yamamoto: Mikuni-so” held at the Asahi Beer Oyamazaki Villa Museum of Art. The space had an atmosphere that was somehow reminiscent of the Leach Bar. Many Mingei works from the Tamesaburo Yamamoto Collection were also displayed at this exhibition.

After the war, Mikuni-so passed out of Yamamoto’s hands, and now it is only at the Asahi Beer Oyamazaki Villa Museum of Art that one can learn about it in detail. In the booklet Mikuni-so: The Early Mingei Movement and Tamesaburo Yamamoto, put out by the museum at the end of last year, there is a photograph of the Mikuni-so kitchen, showing plates and teapots placed openly on shelves, ready to be picked up and used. Mingei works are, after all, everyday vessels and tools.

In 1965 (Showa 40), 37 years after Mikuni-so was completed, the Leach Bar was created, involving many members of the same Mingei circle.

Yamamoto suggested to Leach, “Instead of a monument for you, why don’t we create a room?” Leach later wrote in a letter, “I tried designing a room.” Leach not only sought to harmonize Mingei works with the space, but also paid careful attention to chairs and tables—furnishings that, in Japan, often seemed out of place—in realizing the room that bore his name: the Leach Bar.

Leach’s legacy in Japan: the Mingei Movement and blending of East and West.

In A Potter’s Book (1940), Leach wrote, “It must always be remembered that the dissociation of use and beauty is a purely arbitrary thing. It is true that pots exist which are useful and not beautiful, and others that are beautiful and impractical; but neither of these extremes can be considered normal…” He also visited traditional pottery villages like Matsue, Shussai (Shimane Prefecture), and Onta (Oita Prefecture), working together with local craftspeople at their kilns. He often taught younger potters how to make slipware, a medieval English pottery technique.

In Chapter 9, “ONDA Kyushu” of A Potter in Japan (later translated into Japanese by Soetsu Yanagi), Leach wrote:

“I knew more clearly on this day the underlying motive which has drawn me back to the East once again. It is to rediscover the unknown craftsman in his lair, and to try to learn from living and working with him what we have lost since the Industrial Revolution of wholeness and humility.”

In this way, the blending of East and West found in Leach’s pottery stands out as another driving force behind his involvement in the Mingei Movement. As a Briton, Leach’s perspective on Mingei was perhaps more far-reaching than anyone else’s, and this vision can be seen in the many works he contributed to Japan, as well as in the concept of the Leach Bar.

Text by Hiroki Ko (editor, author)

Examples of Mingei pieces in the Leach Bar

(Works on display may vary at different times)

Flattened vase with Three-Color Glaze / by Kanjiro Kawai

Woodblock print “Fence of the Guidepost” / by Shiko Munakata

Ceramic panel painting “Cornwall Coast” / by Bernard Leach

Ceramic panel painting / by Bernard Leach

Mug / by Shoji Hamada

Indigo textile “Scenes of Okinawa” / by Keisuke Serizawa

Chronology

1887 (Meiji 20)

Bernard Leach was born in Hong Kong. He was taken in by his grandfather who lived in Japan, and resided in Kyoto and Hikone. At age 10, he returned to England. At 21, he entered art school in London. He loved reading the books of Yakumo Koizumi and yearned for Japan.

1909 (Meiji 42)

Leach came to Japan. He began teaching etching at his home in Ueno Sakuragi-cho. His friendship with Soetsu Yanagi began.

1912 (Taisho 1)

Leach, together with Kenkichi Tomimoto, became an apprentice to Ogata Kenzan VI and learned raku ware.

1915 (Taisho 4)

Shotaro Kaga, a Kansai businessman who was also close friends with Tamesaburo Yamamoto, invited Natsume Soseki and his wife to the mountain villa he was building in Oyamazaki.

1917 (Taisho 6)

Leach built a kiln on the Yanagi residence grounds and began making pottery.

1920 (Taisho 9)

Leach ended his 11-year life in Japan and returned to England with his family, accompanied by Hamada, who would become a lifelong friend. He built Europe’s first Japanese-style climbing kiln in St. Ives, Cornwall.

1924 (Taisho 13)

Yanagi visited Hamada, who had returned to Japan, at Kanjiro Kawai’s residence in Kyoto and saw slipware. The friendship between Yanagi and Kawai began.

1925 (Taisho 14)

During a journey to Kishu with Yanagi, Kawai, and Hamada, they coined the new term Mingei (folk crafts).

1928 (Showa 3)

“Mingei-kan” exhibited at the Commemoration of the Enthronement Ceremony: Domestic Products Promotion Tokyo Exhibition (Tokyo, Ueno). After the exhibition ended, the Mingei-kan was relocated to the grounds of the Yamamoto residence in Mikuni, Osaka, becoming “Mikuni-so.” Mikuni-so became the base of the early Mingei Movement.

1934 (Showa 9)

The Japan Folk Crafts Association was established. Yanagi became the first director. Leach came to Japan for the first time in 14 years and during his stay created works at various kilns: Hamada’s in Mashiko, Tomimoto’s in Tokyo, Kawai’s in Kyoto, and Funaki’s in Matsue. He returned to England the following year.

1935 (Showa 10)

The Hotel New Osaka (predecessor of the current RIHGA Royal Hotel Osaka) opened.

1936 (Showa 11)

The Japan Folk Crafts Museum opened. Yanagi became the first president.

1948 (Showa 23)

Journal Nihon Mingei was published, replacing Gekkan Mingei.

1952 (Showa 27)

Yanagi donated all of his private land, house, and furnishings to the Folk Crafts Museum. Yanagi, Leach, and Hamada attended the International Conference of Craftsmen in England.

1953 (Showa 28)

Leach came to Japan via the United States. He traveled throughout Japan and created works in Mashiko, Kutani, Matsue, and Onta. Leach also stayed at the Hotel New Osaka.

1954 (Showa 29)

Shotaro Kaga entrusted the Nikka Whisky business to Tamesaburo Yamamoto.

1955 (Showa 30)

The first Folk Crafts Museum tea gathering was held. There was a Mingei boom around this time.

1961 (Showa 36)

Soetsu Yanagi passed away in May. Shoji Hamada became the second president of the Japan Folk Crafts Museum. Leach made his sixth visit to Japan. A Leach-Hamada retrospective exhibition was held at Osaka Daimaru.

1963 (Showa 38)

Osaka Royal Hotel (currently the RIHGA Royal Hotel Osaka) was established. Yamamoto became chairman and president. Leach conceived the plan for the new hotel’s bar.

1965 (Showa 40)

Osaka Royal Hotel opened. Leach Bar opened. Yamamoto passed away the following year (age 73).

[References: Japan Folk Crafts Museum Handbook, ed. by the Japan Folk Crafts Museum Foundation (Diamond, Inc., in Japanese), etc.]

RIHGA Royal Hotel Osaka,

Vignette Collection

Leach bar

TEL +81 (0)6-6448-1121

West Wing 1F 5-3-68 Nakanoshima,Kita-ku,

Osaka 530-0005 Japan

*This article was featured in the 2016 summer issue of the magazine The ROYAL.